#Tyburn Film Productions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

While I am all for Disney being sued for every little infraction, the fact that getting the actor's estate to sign off isn't enough is kinda wild. Surely if there was a contract for his likeness use after death to a studio/company, the estate would have a copy as well as a history of the payment for said rights conveyed by the contract and would have mentioned something when contacted by Lucasfilm.

I mean, I feel like this is a situation where the lawsuit is going to devolve into proving the validity of the signature on whatever Tyburn has that they are claiming gives them exclusive after death likeness control (which, yeah I get actors are their appearance in many ways but what a weird thing to approach a dying guy asking to buy). Maybe proving that whatever price supposedly was negotiated was actually paid and they aren't just pretending with another money transfer and a good copy paste of a public signature image on a document they made up.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

A number of news reports have surfaced over the last few days pertaining to an ongoing legal action against Lucasfilm and a number of co-defendants being sued over the use of Peter Cushing's likeness in Rogue One. Whilst many presented this case as new, it has actually been ongoing since 2019, and only just reached mainstream media when its latest round reached the UK's High Court. As with many legal cases, not all reporting around the case has been fully accurate - so we will do out best here to unravel the truth. The Defendants The case is being brought by Tyburn Film Productions Limited against five defendants. The First and Second Defendants (Joyce and Bernard Broughton), were the executors of Peter Cushing’s estate, and are alleged to have breached the "1993 Agreement" (more on that later) by consenting to Peter Cushing’s resurrection in Rogue One without seeking Tyburn Film Productions consent. Joyce had been Cushing's secretary since the 1950's and Bernard from the 1970's an unofficial business advisor to Cushing. Cushing would often live with them following the death of his wife Helen, during periods of illness. Bernard and Kevin Francis worked together on Cushing's This Is Your Life television award. Both defendants have passed away since the case was first brought. The Third Defendant (Associated International Management LLP), was Peter Cushing’s (and laterally his estate’s) theatrical agent, it is alleged that they induced the estate’s breach of contract. AIM are one of the leading theatrical agents in the UK, with a number of famous clients including Brian Blessed, Boss Nass in The Phantom Menace. The Fourth and Fifth Defendant Lunak Heavy Industries (UK) Ltd and Lucasfilm Ltd LLC, who stand accused of having been unjustly enriched in respect of the exploitation of rights which they did not hold. Namely image rights to digitally resurrect Peter Cushing. Lunak is the production name for the movie Rogue One, as first revealed by myself on the Jedi News site back in 2014. The Sixth Defendant was the Walt Disney Company, but they have since been removed from the case. Tyburn Film Productions Limited Tyburn Film Productions was formed by Kevin Francis in the early 1970's, the son of acclaimed cinematographer and director Freddie Francis. Kevin's career began as a slaughterhouse employee, but he soon moved into film starting as a tea boy for iconic horror film company Hammer, and worked his way up. He provided the story that eventually evolved into Taste the Blood of Dracula and later became a freelance production manager. His ambition, however, was to be the new Hammer in an era in the 1970's where the horror industry was beginning to fade away. [caption id="attachment_167491" align="aligncenter" width="1275"] Peter Cushing and Kevin Francis on the set of The Ghoul[/caption] The first 'official' Tyburn production was Persecution (aka The Terror of Sheba), a psychological horror story starring Lana Turner, but it was perhaps The Ghoul that was the first 'proper' Tyburn horror. Directed by Freddie Francis, written by Hammer stalwart John Elder and starring Peter Cushing, the supporting cast included ex-Hammer starlet Veronica Carlson, John Hurt, Ian McCullough and Alexandra Bastedo, star of TV series The Champions. Tyburn would also work with Cushing on Legend of the Werewolf, and the The Masks of Death. In 1989, Tyburn would produce the documentary Peter Cushing: A One Way Ticket to Hollywood, essentially an extended interview with Peter Cushing about his life, with clips from some of his best films. It is without doubt that as well as a colleague, Kevin Francis and Peter Cushing were great friends, and Francis had a great affection for the work of Cushing. 1993 Agreement The central claim concerns the right to digitally resurrect (and thus the right to block or restrict the resurrection) of the actor Peter Cushing by technological means. Tyburn Film Productions Limited (the Claimant), alleges that that the use by Lucasfilm of a digital resurrection of Peter Cushing in 2016's Rogue One: A Star Wars Story breaches a contract made between Peter Cushing’s production company, Peter Cushing Productions Limited (PCPL) and Tyburn. Tyburn claims that it has had the sole right to use technological measures to resurrect Peter Cushing under an agreement made in 1993. The agreement was signed in relation to a TV movie that Tyburn was making with Cushing, whilst Cushing was already in ill health with cancer. The TV movie was A Heritage of Horror, it was never competed. Peter Cushing passed away at Pilgrims Hospice in Canterbury in August 1994. The 1993 Agreement contains a clause between Tyburn, PCPL and Peter Cushing: ''If as a result of illness, Mr Cushing's demise or any other reason, without limitation whatsoever or however, the TVM [the TV Movie] is not produced and/or completed and or/exploited, PCPL and Mr Cushing hereby warrant, undertake and agree that neither of them will permit Mr Cushing's participation in any film or programme whereby Mr Cushing appears either in whole or in part other than in person, in or out of any character, by way of Mr Cushing being reproduced by all or any combination of the processes or techniques referred to in subparagraphs (1) through (11) of paragraph (e) without our express prior written consent, which consent we may grant or withhold at our sole and absolute discretion.” The "processes and techniques" referred to include all special effects, computer-generated imagery and any successors to those technologies; thus this would include AI-generated content (a technology developed post 1993) used in Rogue One. Tyburn therefore says that Peter Cushing could not be resurrected by the defendants in Rogue One without their consent. They say that consent from the Estate in the form of the first and second defendants (the Broughtons) was not sufficient because of Tyburn's rights to block anyone else from resurrecting Peter Cushing without obtaining Tyburn's consent (as a result of the 1993 agreement). [caption id="attachment_167492" align="aligncenter" width="750"] Guy Henry Digital Transformation To Peter Cushing[/caption] They claim against the Estate for breach of contract. They claim against the third defendant, who was Mr Cushing's and subsequently the estate's theatrical agent, for inducement of breach of contract. The claimant claims against Lucasfilm and it's production company Lunak for unjust enrichment in respect of the exploitation of the rights that Tyburn says it was in a position to control (''the blocking/restriction rights''). Whilst Tyburn cannot provide permission, that remains with the estate for Mr Cushing, they claim that the blocking rights allow them to effectively override and block any permission given. They were not made aware at the time of entry into, of the agreement between the estate and Lunak / Lucasfilm. Thus their right to block the rights were denied to them. What is not clear to me, and without a legal background, in reading the extract from the contract, is whether Peter Cushing was providing rights regarding all future attempts to resurrect him, or was he intending to refer to use of content from A Heritage of Horror. IF, and it is very much a speculative IF on my part, he meant to provide rights for all future resurrections in film and TV, then why was it contingent on whether A Heritage of Horror was made or not. Effectively IF Heritage of Horror had been completed and released, then Mr Cushing had given no instruction to protect his resurrection. Which would seem a rather bizarre move, if his intention had been to protect himself from that very issue. Why was his instruction contingent on the making of that TV movie? 1976 Agreement Lunak and Lucasfilm has been seeking to strike out / get a summary judgment in the case on the basis that an agreement had been made between Peter Cushing Productions Ltd (PCPL) and Star Wars Productions Ltd in 1976 when the original Star Wars movie was being made (the '1976 Agreement'), which they argued gave them a prior right to use content owned by Star Wars Productions Limited for the purposes of digitally recreating Peter Cushing. Clause 12 of the agreement states: ''The lender [Cushing] gives every consent and grants to the company [Star Wars Productions Ltd] the rights throughout the world (a) to use and authorise others in relation to other reproductions of the artist's physical likeness, recordings taken or made directly or indirectly from the artist's performance, his engagement hereunder." ''… to make or authorise others to make including any other recordings whatsoever of the artist's performance or any part thereof and to exploit the same, and for the purposes of advertising, publicising and commercially exploiting the film or otherwise as the company may desire." Tyburn will seek to argue that this relates solely to Peter Cushing's appearance or performance in Star Wars: A New Hope. Lucasfilm contend that this provides the necessary consent for Peter Cushing's resurrection in Rogue One. Arguments will undoubtedly centre around whether in 1976 the parties contemplated the significant advances in computer technology and CGI, even when ironically Star Wars itself and George Lucas were at the forefront of those developments. The Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 1996 Lucasfilm also contend that Regulation 31 of the 1996 Copyright and Related Rights Regulations (which was the law in place at Mr Cushing's death) provides them with transition provisions between the bundle of different rights that performers accrued under earlier legislation and the performance rights created by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ''New rights: effect of pre-commencement authorisation of copying 31. Where before commencement— (a) the owner or prospective owner of copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work has authorised a person to make a copy of the work, or (b) the owner or prospective owner of performers' rights in a performance has authorised a person to make a copy of a recording of the performance, any new right in relation to that copy shall vest on commencement in the person so authorised, subject to any agreement to the contrary." 2016 Agreement Alternatively, Lucasfilm also contend that they acquired the right under another agreement, made on 10th February 2016, between the First and Second Defendants (the Broughtons) acting as the estate for Peter Cushing and the Fourth Defendant (Lunak), (the "2016 Agreement"), specifically made in relation to the digital recreation of Mr Cushing in Rogue One. A sum of £28,000 was paid to the Estate, making Lunak "bona fide purchaser for value" of the rights to Cushing’s image. By being a bona fide purchaser for value, Lucasfilm will argue that they thus were not unjustly enriched. They made a payment as an expense in order to benefit from the right acquired, thus any income generated was off the back of that expenditure and thus can't be deemed unjust. Case History / And Verdict To Date In 2019 Tyburn, through solicitors, contacted Lucasfilm, maintaining that Rogue One had been made using a digitally resurrected Peter Cushion without the permission of Tyburn and therefore in breach of the "1993 Agreement." A pre-action disclosure order was made against the Estate of Peter Cushing on 2 July 2021 requiring disclosure of its agreement with Lunak / Lucasfilm. On 2 August 2021 the current proceedings were issued, raising a claim for breach of contract against the Estate, a claim for procuring breach of contract against the Third Defendant and a claim against Lunak / Lucasfilm for unjust enrichment by receiving the licence to recreate Mr Cushing from the Estate and/or the exploitation of that licence. Following a hearing on 22 November 2023 the attempt to summary dismiss the case was initially dismissed by Master Francesca Kaye in December 2023 and she instructed it to go to trial, but permission to appeal was granted to Lucasfilm by Mr Justice Michael Green in February 2024. The appeal was heard by Tom Mitcheson KC, sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court on 9th September 2024. He said he was “far from persuaded” that Francis would succeed, but added: “I am also not persuaded that the case is unarguable to the standard required to give summary judgment or to strike it out. “In an area of developing law it is very difficult to decide where the boundaries might lie in the absence of a full factual enquiry.” Thus he denied the move for a summary judgement / dismissal of the case, and the case will move forward to trial. However, based on comments made it seems that Lucasfilm and the other defendants have strong grounds in their defence and the claimant faces an uphill battle to prove their case. Background Directed by the UK's Gareth Edwards, Rogue One is the first standalone movie in the Star Wars franchise, serving as a direct prequel to the events of the original Star Wars movie, A New Hope. The plot revolves around a ragtag group of Rebels who team together to steal the original Death Star's blueprints, which eventually allows the Rebel Alliance to identify a weakness and destroy the Imperial super weapon at the conclusion of A New Hope. As Grand Moff Tarkin, Peter Cushing, was the commanding officer of the Death Star, making his role central to A New Hope's plot but whilst small, pivotal in Rogue One. Rogue One's cast included Felicity Jones as Jyn Erso, Diego Luna as Cassian Andor, Ben Mendelsohn as Orson Krennic, and Mads Mikkelsen as Galen Erso. It was a commercial box office success, earning over $1 billion globally, and spawned the Disney+ spin off TV show, Andor. Disney has regularly used digital technology in de-age or resurrect actors. Carrie Fisher appeared in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker three years after her death in 2016 through a mix of CGI and altered unused earlier footage. She also appeared de-aged in Rogue One via CGI and the physical performance of Ingvild Deila. James Earl Jones, who died aged 93 this week, had already had his voice digitally manipulated to deliver lines for a 2022 Disney+ Star Wars TV series, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and a de-aged Mark Hamill appeared in The Book of Boba Fett and The Mandalorian. [caption id="attachment_35665" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Ingvild Deila as Princess Leia in Rogue One[/caption] With the proliferation of AI tools in filmmaking, the ease of recreating a deceased actor’s likeness is likely to only increase. In response to this evolving technology, the state of California has now passed a law that requires consent from performers for AI to use their likeness after their deaths. The UK where much of the filming for Star Wars takes place has no such legislation currently in force. As for the ethics of using digital resurrected actors, thats a whole other debate...

0 notes

Photo

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GHOUL (1975) – Episode 182 – Decades Of Horror 1970s

“Well, it can’t be Human, can it? It feeds on Human flesh!” Apparently, they hadn’t heard of cannibals? Join your faithful Grue Crew – Doc Rotten, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, and Jeff Mohr – as they check out The Ghoul(1975), a film with many ties to Hammer, yet, not a Hammer film.

Decades of Horror 1970s Episode 182 – The Ghoul (1975)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

A former Priest named Dr. Lawrence harbors a dark and horrible secret in his attic. The locked room serves as a prison cell for his crazed, cannibalistic adult son, who acquired his savage tastes in India during his father’s missionary work there. Lawrence fears that his son will escape to prey upon the effete guests at his rural English estate during a cross-country auto race.

Director: Freddie Francis

Writer: Anthony Hinds (as John Elder)

Producer: Kevin Francis

Selected cast:

Peter Cushing as Doctor Lawrence

John Hurt as Tom Rawlings

Alexandra Bastedo as Angela

Veronica Carlson as Daphne Wells Hunter

Gwen Watford as Ayah

Don Henderson as The Ghoul

Ian McCulloch as Geoffrey

Stewart Bevan as Billy

John D. Collins as “Young Man”

Dan Meaden as Police Sergeant

You all remember Tyburn Films Productions Ltd., right? Wait, maybe not… With only just over a handful of films, this British company quietly began in 1973 with Tales that Witness Madness (uncredited), and, in 1975, they churned out a pair of gothic horror films that look very much like Hammer, Amicus, or even Tigon. Directed by the legendary Freddie Francis and featuring Peter Cushing, John Hurt, and Veronica Carlson, The Ghoul (1975) is one of these two creature features. The other is Legend of the Werewolf (1975). Join the Grue-Crew as they determine how well this film stands up to its contemporaries.

At the time of this writing, The Ghoul is available to stream from Tubi.

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1970s is part of the Decades of Horror two-week rotation with The Classic Era and the 1980s. In two weeks, the next episode in their very flexible schedule, chosen by Chad, will be Pigs! (1973, aka Daddy’s Deadly Darling), the film with a thousand titles. Well, almost.

We want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror 1970s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

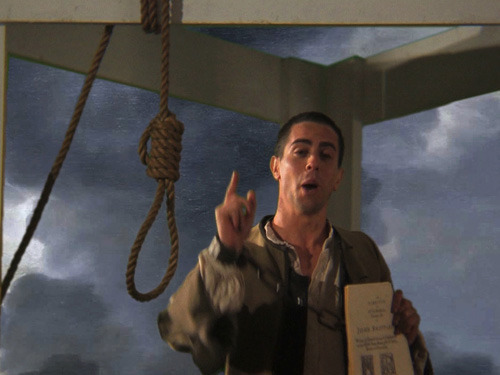

Notes on “The Last Days of Jack Sheppard”: Capital Crimes and Paper Claims

[by Benedict Seymour / Mute]

Introduction by Rogue: This film was an art project originally screened at the Chisenhale Gallery, London, in 2009. From the artists’ site: “The Last Days of Jack Sheppard is based on the inferred prison encounters between the 18th century criminal Jack Sheppard and Daniel Defoe, ghostwriter of Sheppard’s ‘autobiography’. Set in the wake of the South Sea Bubble of 1720, Britain’s first financial crisis, the film is a critical costume drama constructed from a patchwork of historical, literary, and popular sources. It traces the connections between representation, speculation and the discourses of high and low culture that emerged in the early 18th century and remain resonant today.”

There were no commercial screenings, it has no IMDB entry, and as far as I can tell it can’t be downloaded, legally or otherwise. So I’m reposting here the review of a film/art installation that I haven’t seen and probably never will, and that YOU haven’t seen and probably never will, because it’s a damn interesting story. Also, long post.

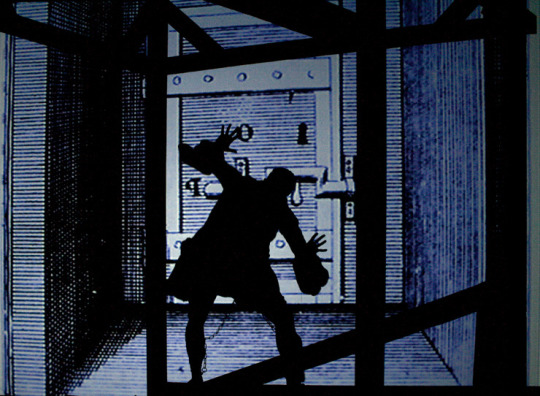

The Last Days of Jack Sheppard (2009), directed by Anja Kirschner and David Panos, retells the story of a proletarian hero of the early 18th Century who ending his days at the gallows – ‘the triple tree’ – in Tyburn in 1724, was executed for theft at the dawn of financialisation.

Jack Sheppard wasn’t much of a thief. Serially incarcerated during his short life, he won fame for his ingenuity and implacable dedication to getting out of gaol. This is years before Houdini, with his spectacularised escape artistry and proto-Fordist routinised liberation. It is years before David Blaine, who inverted the trope of getting free into feats of hyper-visible confinement endured. Jack’s very public demise is furthest from but for us also closest to the telematic death and redemption of Jade Goody, a working class woman who, like Jack, also found fame in dissolution.

Unlike Jade, however, Jack stood for a certain resistance to commodification and the intrusion of the State into one’s intimate processes of self-reproduction.1 Like her he rose to fame in the wake of a suddenly deflated financial bubble. The Last Days of Jack Sheppard plays on the interconnections between his acts of criminal reappropriation and the speculative adventures of the wealthy during the South Sea Bubble of 1720. As much as anything, Jack’s notoriety was about the contrast his crimes made with the legally sanctioned scams of his social superiors; his bravery, fortitude, skill and cunning versus his superiors’ petty self-aggrandisement and greed. Jack also remained independent of corrupting tendencies within his own class and refused to join in the rackets of Jonathan Wild, self-appointed ‘thief-taker general’.

For these and other reasons we will come to, Jack was one of the first heroes of popular culture. His ghost-written biographical Narrative appears as an early act of proletarian public speech. A posthumous publication, the Narrative is based on the words of a man condemned to death; a man escaped and recaptured who is given the right of representation only when he has nowhere left to run.

Near the beginning and end of the film the notorious housebreaker and escapologist (four times escaped from prison, four times recaptured) invokes his right to speak. He holds up the manuscript of his memoirs to the crowd as he stands before the gallows, a dialectical image of the decisive forces of his age. The scene brings everything together – capital and capital punishment, money and representation, the mob and their hero. Jack steps up onto the platform to have the last word, to give his own account and put right earlier misrepresentations. However, the film sardonically notes that this last gesture of self-assertion is already, also, a piece of advertising. Jack’s publisher Mr Applebee is at hand to tout the completed Narrative – ‘available for 6 pence only from Applebee’s’. In the background, as we shall see, there is the anonymous ghost-writer of the text, Daniel Defoe.

It may be considered a moment of resistance, a claim to rights that were not supposed to be issued to people of Jack’s class. As such it is also an attempt to use the bourgeois representational apparatus to get something material back – control over his own history and a legacy for his mother. This last raid on the emerging finance/culture nexus is carried out within the terms of the law and of the market. Like the stocks and bonds of the bankrupted stockjobbers glimpsed in the wreckage of the South Sea Scheme at the beginning of the film, Jack’s Narrative is itself a kind of ‘paper claim’ on value. Behind it lies a contract, and a title to sales revenue, but in itself the Narrative is a fiction, a projection of what his life will have meant. Furthermore, Jack is not the real, or at least the sole, author. The film’s diegesis continues and exacerbates the logic of displacement by putting into his mouth words that others would only have read on the printed page, pointing up the artificiality of the mise-en-scene and, by extension, of the public sphere.

Jack’s moment of free and direct expression, of the right to tell one’s story and give one’s own account of one’s self, is also the moment of commodification. Destitution recapitulated. Alienation consolidated by claims of complete transparency (Defoe’s vanishing mediation). The moment of truth is the moment of fiction, of a constitutive falsehood analogous to the wage labour contract in that it is both ‘authentic’, legally recognised and a kind of betrayal of at least one of the consenting parties. Jack becomes a virtual player in a textual construct, enabling us to retell and rework his story, but objectifying and distorting his necessarily open-ended subjectivity. Death launches him on the literary market. Analogies to paper money and credit here are not accidental: representation opens up the possibility of derivatives, variants, meta-fictions.

The act of representing one’s self – as the film explores – depends on just such objectifications, a process of displacements and substitutions which put the speaker’s identity and status (living/dead, rich/poor, etc.) in doubt. Jack breaks through the social repressions of his day to speak up for himself and, by extension, his class, but he is also spoken for. His words are put to work. The future development of working class struggle to escape from capitalism is foreshadowed here. The question is implicit throughout – how does the subject/object of history, neck in the noose and facing extinction (or perhaps the mutual ruin of the contending classes), get out of this one?

As in life, he had to alienate his considerable skills as a carpenter in the service of others’ accumulation of capital, so in death Jack’s voice is ventriloquised and exploited by Messers Applebee and Defoe for their own ends. Equality is the very form of inequality; the contract guarantees the subordination of the economically dependent and the reproduction of their alienation. Jack makes history, or at least his history, but not in conditions of his own making. And what will history make of him? The film is hyper-conscious of the potential and risks of myth making, yet in order to pose the question of Jack’s legacy, of his contemporary significance and indeed the future of his class, it is necessary to put him in the frame; the film has to borrow and trade on his legend.

The early 18th century represented here is an age of ‘projections’, of new financial abstractions, schemes and scams, exerting an increasingly autonomous force in social life. Jack’s story, at once a critique of the self-contained world of the stock exchange, the Mansion House and the coffee house, is itself a highly mediated claim to authenticity, a work constructed by Daniel Defoe giving the illusion of a first person account. However, true to Jack’s own language and history, it is necessarily a work of (real) abstraction. For a growing market, Jack’s life has become a kind of ‘structured investment vehicle’, a spectacular commodity with an existence independent of the unruly mob who flocked to his hanging. In death, his social mobility is potentiated.

Jack’s rebirth (or undeath) as a literary figment and popular hero, like the floating of a new concern, is a hostage to the market and to the stories people will construct as derivatives of his ‘authentic’ paper representation. Once written down, he is no longer free to determine his story. The film itself is one such derivative, taking as its premise a hypothetical struggle between the Narrative’s two authors – the ghost writer and ghost-written, Defoe and Sheppard – over the content of the biography. By positing this ur-narrative or pre-textual struggle the film is able to reopen what the Narrative tried to close. It is a narrative back-projection which underlies and echoes the film’s other projections, its allegorical/art historical décor made up of prints, paintings, drawings and other artefacts from the period.

Long ago, Frederic Jameson identified postmodern culture’s ‘renarrativisation of the fragment’ as a kind of recycling, reinscription and domestication of modernist practices of disjunction. What distinguishes The Last Days use of parody from this form of blank referentiality is its heightened awareness of the economic determination of and struggle over signs. Where Jameson sees in postmodern culture’s abstraction and reflexivity an analogy to finance capital’s attempt to defer and get around the underlying tendency to crisis in capitalist production by proliferating virtual capital, this particular art work turns the logic of cultural looting in on itself. The result is an emphasis on the perpetual presence of economic relations of domination in capitalist culture tout court. The struggle between Jack and his literary representative is not a mere conceit by means of which to squeeze a new work out of an old one, an ‘exotic literary instrument’ that yields a domesticated and carefully captioned blast from the past. Instead it pushes renarrativisation into overdrive, offering a web of analogies and historical allegories.

By enquiring into the effectivity of signs, the performative power of fictions – economic, literary, biographical – the film is also alert to the way ‘paper claims’ function primarily as ways of appropriating the (rest of the) material world. Money is essentially a title to future value, a ‘licence to loot’ insofar as the paper titles to capital which capitalists deal in always project ahead of the world, ahead of existing value, through the process of capitalisation. Signs, however apparently free-floating and autonomous, tend to intersect in the most brutal ways with processes of accumulation, equivalent and non-equivalent exchange. Paper claims exact work and life from the labouring bodies they command. In the case of the film, the key moment being the separation of peasants from the land and the production of the urban proletariat of whom Jack is a part. Money, State and the banking system are results and, it should be stressed, products of the (perpetually renewed) dispossession of the poor from all independent means of subsistence. Paper claims are worthless without the State to back them up, and the projections of the financial elite are likewise predicated on a brutal ‘framing’ of the poor.

This brings us back to the triple tree. Execution is the most profound form of recognition which the ruling class can offer one such as Sheppard. It’s also, however, a way of negating identity completely. Capital punishment makes the criminal at once particular and equivalent. Use of the gallows was calibrated around the price of commodities, and hence the socially necessary labour time reappropriated by the malefactor and unreliably echoed in the (jurors’) estimate of the prices of the stolen commodities.2 But the gallows were indifferent to the arguments and aphorisms that a proto-literary figure like Jack was capable of (‘One file is worth all the bibles in the world’). Jack’s (illicit) claims are answered by his definitive transformation from subject to object – the inversion on which capitalism runs made horribly explicit. The ‘moment of [his] dissolution’ is the moment of his complete reification, and, with the help of Defoe and Applebee, the moment at which he gains access to the official means of representation, becoming the subject of a new kind of separation, a second order of (linguistic) enclosure. His death sentence and its execution opens up the space of representation, the dimension of fiction, fantasy, financial projections and speculative futures. Indeed, as we have said, Jack is ‘floated’ as much as hanged and his Narrative becomes the stuff of, or rather for, Legend. A story is born with the death of its protagonist, the Narrator (in the manner of a film noir such as D.O.A.) is already posthumous. Like Jade who survived to read her own obituary, there is something zombie-like about the public proletarian, not lacking in wit, far from wordless, but at the same time, as Applebee puts it, ‘doomed’. The sympathy of the public sphere for marked men and women is already, at this historical moment, the most suspicious thing about it.

There is something rather ‘aesthetic’ about this final instant, then. To quote one of the newspapers of the day, Sheppard was hung up and ‘dangled in the Sheriff’s picture frame’ for 15 minutes. ‘The sheriff’s picture frame’ makes clear the tacit connections between artistic and literary representation and the State’s repressive apparatus. Beyond any Warholian undertones, the link between execution and celebrity is not just via the struggles over the body of the malefactor, the crowd’s identification with the victim or the ballad sellers’ narration of their life and times. In fact, the gallows are aesthetic insofar as it constitutes a crude means for communicating a message to those that can read Jack’s broken body. The State itself requires notoriety to get its point across. This is spectacular language aimed at the (mostly illiterate) early proletariat. Not for them Jack’s ghost written Narrative.

The message is the imposition of work. Commodification uses death to communicate its imperatives to the living through the mediation of exemplary delinquents. As the film presents it, Jack is an escape artist captured first by the fascinated artists of the aristocracy (Thornhill paints Jack’s portrait while the felon is chained up in Newgate, shades of Fassbinder’s Fox and his Friends, here) and then definitively by the art of the State. As Peter Linebaugh frames it in his great book The London Hanged, the triple tree was not so much the final stage for disposal of society’s ne’er do wells, as one of the foundations of the economy. Capital punishment was a part of the production and reproduction of the poor as workers, it was there to teach people a very definite lesson. Founded on the originary violence of primitive accumulation – the separation of people from their collectively held property through the enclosures – early capitalism attempted to instil in those that produced its wealth the necessity of toil. Those who refused to submit to the imperative of making their living by taking what they needed to subsist – or like Jack, flaunting a desire for luxury deemed out of his social reach, luxury beyond reason or measure – would be made an example of. The triple tree was the most important prop in a theatre in which the insubordinate were turned into the unfortunate protagonists of a cautionary tale.

But the State did not have complete control over this stage or the stories told about it; both the criminals and the mob were given an opportunity by the very public nature of the spectacle. Jack’s speech in the film sums up the way in which the stage of instruction was being turned into a site of contestation, a place in which the poor might talk back and challenge the ongoing process of separation by which work was imposed.

Revolts at the points of instruction, punishment and incarceration were in turn providing the raw materials for goods in the literary market place, another node in the production and circulation of commodities. The spiral continues, from enclosure to escape, re-enclosure to re-escape, re-escape to re-enclosure. Remorseless, and contingent, one recalls Marx’s famous formula for the mutation of money into more money: ‘M-C-M’. Capital wants it to continue in a seamless cycle, but in reality there are many obstacles to valorisation ��� Jack is just one example.

During the course of the film the dialectic of representation gets turned around one way then the other. Defoe may have tried to make an example of Jack, a lesson that crime doesn’t pay, that corrupting influences lead him astray, or, more subtly and presciently, that within even the worst criminal there is a kernel of industrious ingenuity that, carefully harnessed, can and should be put to work for expanded accumulation. The film shows Defoe struggling to impose his sense of Jack’s story, to tell something more than a simple morality tale, or rather to invent a new morality able to move on from the dizzying loss of balance produced by the South Sea Bubble. Defoe is straining forward to something like Adam Smith’s conception of civil society, but remains confused and disoriented by the financially-accelerated rise of his own class – not to mention Jack’s. The film makes this drama perhaps even more central than Jack’s own (circular) narrative of incarceration and escape. If he could redeem the whore Moll Flanders and turn her into a kind of self-made woman, perhaps Defoe can reconfigure Jack as a post-Bubble figure of mis-directed industry.

Half the time Defoe is winning, half the time Jack. The film leaves the struggle open, but history suggests that Defoe’s successors did find a way to put Jack’s drive to exit (not to mention his right to a voice) to work. Defoe anticipates Adam Smith and Smith, both Marx and Keynes. All that’s solid melts into air, says a Frenchman surveying the ruin after the collapse of the bubble at the start of the film. But this ‘dissolution’ produced the new financial instruments, the perfection of the division of labour, the growth of industrial capitalism and the rationalisation of the working class, with the Socialist movement the most ambitious and contradictory form of integration. Today, both the bubble and the bureaucrats are in a state of collapse, yet, as the film’s less than exuberant mood implies, the proletariat has not yet found a way to get back on (and/or, off) the stage of history. Instead, they have a gallows look about them.

In this respect, Sheppard is a salutary reminder of the potential of working class insubordination, its ability to posit itself as a ‘self-subsisting positive’, not the negation of the bourgeois negation reproduced by the socialist movement. On the other hand, once one grants a certain autonomy to the working class, one has to acknowledge that capital, in our era, has been only too keen to leave the poor increasingly to their own devices. (At least when it comes to welfare provision; when it comes to surveillance, it’s another matter).

As Peter Linebaugh tells it in The London Hanged, Jack’s popular appeal was based on a shared experience as much if not more than symbolising some utopian return to a life before, let alone beyond, capitalism. Jack stood not only for the possibility of turning the tables on the owners of capital but for the daily escapology that the poor needed to practise in order to survive. According to economic historians of the period, the poor’s ability to subsist at all remains a mystery. Crime was not so much a deviation from the path of righteousness as an essential part of the daily journey of self-reproduction. Jack’s may be a story of freedom, as Peter Linebaugh says, but it is also about the way in which proletarian escape can and must itself become a part of capitalism’s continuation. One recalls Mike Davis writing in Planet of Slums about the contemporary form of this ‘wage puzzle’:

With even formal-sector urban wages in Africa so low that economists can’t figure out how workers survive (the so-called low-wage puzzle), the informal tertiary sector has become an arena of extreme Darwinian competition among the poor.

To put it another way, the ongoing attempt to break the law of value, to live more than is allowed, is from the beginning, and again today, an increasingly central part of capital’s calculus. Rather than honouring the principle of equivalence on which commodity exchange is founded, from the beginning capital has depended on short changing those that produce and constitute value. Jack may have taken more than was deemed his due, breaking the principle of equivalence by running away with the means of production or stealing a silver spoon destined for the unproductive consumption of his betters, but capital also assumed – one could say it insisted – that people would find ways to exist and to labour on less than they were owed.

The film proposes a rhyme or homology between this early period of capitalism in which the wage was barely operative, before the stable establishment of capital’s rules, and our present moment in which the rules appear irreparably bent and in which a second financial revolution is collapsing into a crisis of unprecedented proportions. The process of financialisation is presented as co-existent with that of primitive accumulation, mutually reinforcing.

Jack’s birth as a fictional character coincides with a generalised fictionalisation of identity and a simultaneous dematerialisation and reification of its physical and linguistic props. As money replaces land and wealth is dissolved into economic representations, gold is displaced by coin and in turn paper, and ready money by public credit, the subject is (forcibly) liberated from the continuities and fixities of feudal society. As the film suggests, this involves the transformation of ‘character’ into ‘mere’ writing; myths of depth and substance are under attack, the self as a performance or improvised script comes to the fore. Finance itself is positioned as one of the key, possibly the key, solvent of feudal social relations. Those that today call for a return to a healthy, productive capitalism purged of speculation overlook not only the constitutive place of finance capital in any capitalism whatsoever, but also the way in which speculation is a necessary condition not only for modern thought but for modern praxis tout court. To be precise, for that material praxis which Marx identifies some 130 years after Jack’s pioneering efforts in excarceration. The apprehension that humans are the source of the value/s they live by, and that the reproduction of the world in its totality is down to our sensuous activity is the dangerous secret behind commodities such as Jack.

Thus, fictitious capital is an agent that not only produces a new fictitiousness and fluidity of identities but also, potentially, contributes to the volatility of social relations that makes possible the creation of new forms of life. The aristocracy grabbed the opportunities (and took the risks) which came from the rise in capital by mortgaging their land and creating a sort of trangenerational stipend, which was a life saver for a class in decline. The poor, however, were brutally separated from their own communal holdings of land and had to take back what they could through a process of imposed improvisation. Jack is a figure for the unmanageable excess generated in the process, an unforeseen by-product of a society governed by the imperative of capital accumulation. As such, his primitive challenge to capital is not so much a residue of the feudal era but a brand new product, yet to be mastered and, today, no longer subject to the dismantled and decaying apparatus of labour representation.

Capital has been dependent on breaking its own law of value in both eras, pushing to impose its terms of exchange and to hold workers to written and unwritten contracts while finding ever new ways to get around the iron equation between value and the socially necessary labour time for its reproduction. Corruption is not only the source of innovation (pace Bernard Mandeville, Adam Smith, Giovanni Arrighi and Antonio Negri) it can also be a sign of a system’s decadence. While corruption was the talk of the whole nation for much of the post-South Sea Bubble era, up to and including the appearance of Jack on the scene, the grotesqueries of non-equivalent exchange were only fully perceptible against the intimations of equality emanating from the very logic of the market. The aristocratic critics of capitalist greed deployed a feudal morality which they themselves found increasingly impossible to inhabit, while satirists such as Swift already noted the unfairness and cruelty of the new society, even as they hankered for a restoration of more stable forms of domination. In Jack’s day the dissolution of a stable hierarchical social order based on landed property is the most obvious and the most encouraging, result of the rise of financial and mercantile capital. Power was becoming visible, status and influence could be bought, privileges were being transmuted into more nakedly economic forms of domination.

Corruption, and the financial crisis released by the collapse of the South Sea Bubble, would become part of the movement toward expanded social reproduction which capitalists themselves (think of Thomas Malthus’ gloomy anticipation of death by horseshit) could hardly comprehend at this point. For all its intrinsic brutality, the imposition of the form of abstract labour on work just beginning in Jack’s day. This would see not only the rationalisation and disenchantment of social existence in its totality but the creation of the material conditions for hitherto unknown self-determination and abundance – given that the dispossessed reappropriate and transform the forces and relations of production. In our day, corruption and delegitimation seem to have undermined fixed authority and ensured the reproduction of a decadent system; both capital and its social democratic opposition (‘the left wing of devalorisation’) are discredited but the working class have suffered greatly through the concomitant process of non-reproduction.

Defoe’s scheming to imagine a way of putting Jack’s exuberance to work points toward both a new form of enclosure – from industrial production down to Fordist devalorisation through the supervision of every aspect of the workers’ reproduction — and a more rational form of social existence. By contrast those writing the working class’s scripts today are rarely capable of imagining a better world even in their own meagre terms. As such Jack’s moment rebukes our own; the social imagination fired by his escapes needs to be reawakened through modern day excarcerations. Although these may have to take apparently Blaine-like forms: occupations, refusals to move, the assertion of our rights in parts of the social factory that capital is now trying hastily to dismantle. Again, these rights will not necessarily be enshrined in law, and will involve workers crossing the line. Jack’s opportunism is also salutary. One can use the law, protect oneself where necessary, know the law better than one’s lawyers. But one will also need to keep alive a healthy sense of the law’s fictitiousness, its paper claims to a justice which can only be material.

The paradoxical message of Jack Sheppard’s fugitive art in an age of faltering globalisation and desiccating liquidity is that fixity and self-enclosure can be a tool of liberation; a first, if necessarily transient, step toward a greater excarceration. In the year of the Lyndsey and Visteon workers’ struggles, we are returned to the ambiguous legacy of the integration of the proletariat into structures of representation with a vengeance.3 While some dismiss any concern with the fate of the residual industrial working class as chauvinistic or narrowly sectarian, a fetish for manual labour or racist preference for defending the struggles of those with something rather than nothing to lose, it is worth considering how – like Jack on the gallows, facing death – the almost-posthumous workers of the world can also send out insurrectionary signals when they refuse to go gently into the lousy night. The Last Days of Jack Sheppard traces the implications of a valediction without reconciliation, the power of refusal in extremis as the beginning as well as the end of something.

Footnotes

1 It could be that what was truly representative about Jade’s death was that it was an avoidable tragedy resulting from neoliberalised UK health care’s growing focus on policing behaviour over the treatment of illness. If her cancer had received the same attention as her subsequent demise (not to mention the ongoing saga regarding her moral status, etc.) there would have been no life-affirming, emotional franchise, no fictitious capitalisation on her death. Some would rather see the death-fest as a sign of our emotional evolution and progress (as with the manic mourn-in for Princess Diana) rather than an index of social decadence. However, though Jade’s death put cervical cancer check-ups back on the agenda for younger women, one should ask why they weren’t making regular trips to the doctor in the first place. Responsibility is shifted onto the patient and away from the ‘service’ provider/public-private State. The flip side of this contraction of social reproduction is a corresponding financialisation of death. Max Keyser notes that with the rise of entertainment futures trading there is now a corresponding spate of death rumours and death threats circulating as a result of ‘death speculation’ and ‘death pools’, as traders attempt to sell short Hollywood actors and other A(AA?) list stars. Market manipulation is spreading from the stock exchange to the entertainment industry as the crisis deepens.

2 ‘We observe a relationship between 10d. and a whipping, between 4s. 10d. and a branded hand, and between large sums of money and a hanging … they are only imagined figures of account [… but …] the consequences of these sums upon the bodies of the offenders were very real.’ In Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century, Verso, 2003, p. 82.

3 As so often, union representatives have played an at best ambivalent role in the current conjuncture. Though union members and shop stewards made much of the running, particularly in the mobilisations around the Lyndsey refinery wildcat strikes, union convenors and bureaucrats acted largely as a break on the development of struggle at the occupied Ford-Visteon plants. Indeed, in a manner analogous to the British State’s cocktail of negligence and interference when it comes to welfare provision, ‘representation’ here meant supplying unreliable legal advice to union members and fear-mongering about the repercussions of stepping beyond the law whilst failing to provide material support and funds. For an excellent account and analysis of the struggle by workers at the Ford-Visteon plant in Enfield earlier this year see Ret Marut’s, ‘A Post-Fordist Struggle: Report and reflections on the UK Ford-Visteon dispute 2009’, June 9 2009 (8)

#long post#Benedict Seymour#Jack Sheppard#Daniel Defoe#The Last Days of Jack Sheppard#analysis#big thief little thief#the phantom of liberty#swinging from the gallows tree#the right to be lazy#trs

0 notes

Text

Legend of the Werewolf - UK, 1975 - reviews

Legend of the Werewolf – UK, 1975 – reviews

Legend of the Werewolf is a 1975 British horror feature film about a young man that turns into the titular beast and murders men who frequent a brothel.

Directed by Freddie Francis (Tales from the Crypt; The Vampire Happening; The Skull; et al) from a screenplay written by Anthony Hinds [as John Elder], the Tyburn Films production stars Peter Cushing, Ron Moody, Hugh Griffith, David Rintoul and…

View On WordPress

#1975#British#film#horror#Hugh Griffith#Legend of the Werewolf#movie#Peter Cushing#review#reviews#Ron Moody#Tyburn Films

0 notes

Photo

The Future Of London, 1980's Style

Listicles are nothing new. Back in 1988, the Illustrated London News ran a special issue looking to the future of the city. Inside, a roll-call of famous names picked out 50 ways to improve the capital. Contributors included Melvyn Bragg, Auberon Waugh, Sebastian Faulks and Lady Longford (which famous face wrote which suggestion is not revealed). What did they choose? And did any of these things get fixed in over the next three decades? We've selected 10 of the more interesting ideas for a look-see. 1. Civilise the underground The tube was a grubby place in the 1980s, thanks to years of underinvestment. The very first item on the wishlist called for the tube (and its passengers) to be smartened up. Line items include a ban on 'Walkmans of every description', outlaw eating and drinking on the tube, celebrity PA announcements (Lord Olivier at Leicester Square), screens to introduce new films or stage productions, and automatic ticket checking machines. The best idea of all: paint the trains to match the line colours. Did it happen? Partially. The screens are now commonplace, and all tickets can be automatically checked. TfL has even dabbled with celebrity announcements. Impractical though it'd be, we'd love to see the line-coloured trains. 2. Encourage more firework displays The article bemoans how continental countries let off fireworks for any old celebration, whereas London limits them to 5 November. More please! Did it happen? Emphatically, yes. London's New Year's fireworks are now among the world's most noted. Meanwhile, the multicultural nature of the city has seen an increase in firework displays for the festivals of different faiths. 3. More inscriptions on streets and buildings One example from North Greenwich. Image by the author. The suggestion is to inscribe the stones of London with choice cuttings from novels, plays and poetry. Every stroll would be a literary adventure. Did it happen? To some degree. While not exactly encountered on every stroll, it's not uncommon to find quotes and bon mots inscribed on walls and pavements. Poems on the Underground, launched in 1986, was already doing something similar. 4. Remove all the Nuclear Free Zone plaques During the 1980s, '16 barmy London boroughs' declared themselves Nuclear Free Zones by attaching plaques to 'every spare lamp post'. It was a way of telling the Ruskies not to bomb Haringey, say, because it didn't harbour any nukes. Did it happen? (Removal of the signs; not the obliteration of Haringey.) Apparently so, as we've never stumbled across one of these plaques. We're guessing they slowly disappeared following the end of the Cold War in the 1990s. A forgotten chapter in London's recent history. 5. Hold a pigeon shoot in St James's Park The feral pigeon population of the West End was out of control in the 1980s. The proposal would allow the public to take potshots at the pests in the Royal Park once every month. This would not only reduce the pigeon population, but also 'provide an outlet for the frustrations of lunching civil servants' — almost literally killing two birds with one stone. Did it happen? Of course not. Although a ban on pigeon feeding was later introduced to nearby Trafalgar Square by then-Mayor Ken Livingstone. 6. Return the Temple Bar Temple Bar, back in London. Image by the author. The famous gateway, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was removed from the western end of Fleet Street in 1878, as it was known for causing a traffic bottleneck. It was rebuilt in Theobalds Park, Hertfordshire, where it had fallen into a shabby condition by the time of this article. Did it happen? YES! The whole gate was shifted once again in 2004 and re-erected in Paternoster Square near St Paul's. It is a rare example of a building that has stood in three locations. 7. Brighten up Buckingham Palace The author bemoans the 'featureless Victorian frontage' (it's actually from 1913) that greets tourists to the Palace. How to relieve the tedium? 'The construction of something like a giant cuckoo clock on the balcony from which life-size models of the royal family would parade on the hour'. Did it happen? Sadly not. 8. Retractable roofs for sporting arenas Olympia's retractable roof. Image by the author. Houston and Toronto have retractable roofs on their sporting arenas. Why should we suffer our sporting events to be cancelled by a bit of rain? Build more roofs! Did it happen? Unbeknown to the author, London already had a retractable roof at Olympia, though that's not usually considered a sporting venue. In the years since the article, both Wembley and Wimbledon Centre Court have gained retractable roofs. 9. Restore the lost rivers of London The River Fleet as it looks today. Image by the author. Tyburn, Walbrook, Fleet... the names of London's buried rivers are well known. According to the article, 'There seems to be no reason why considerable stretches of lost rivers should not be disinterred and landscaped'. Did it happen? No. There is a reason. Considerable stretches of lost rivers are serving a vital role as part of the sewer system. Do we really want to mess with that? The notion is revived every few years, most recently by Boris Johnson. 10. Rebuild London Bridge Old London Bridge, in St Magnus the Martyr church. Image by the author. Modern London Bridge, opened in 1973, is a sturdy, functional span, but not one anybody could fall in love with. We need to recreate the medieval London Bridge, complete with its houses and shops (though, presumably, the heads-on-spikes can stay in the past). Did it happen? No. Instead we got the attractive Millennium Bridge and Golden Jubilee bridges. Nevertheless, a habitable bridge over the Thames was yet another idea suggested by former Mayor Boris Johnson, in 2008. Did he have a copy of this 1988 article filed away in his office? 50 Ways to Improve London is available online via the British Newspaper Archive, and requires a paid subscription. Archive images from that article courtesy of the British Library Board, (c) Illustrated London News Group.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/londonist/sBMe/~3/paU5lE0AWBc/10-ways-to-improve-london-as-suggested-in-1988

0 notes

Text

THE BROTHERHOOD OF SATAN (1971) – Episode 181 – Decades Of Horror 1970s

“Not your baby!��Our baby! Satan’s baby!!” You seemed like a folksy small-town doctor but it turns out, you’re really the head, satanic dude. Join your faithful Grue Crew – Doc Rotten, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, and Jeff Mohr – as they check out The Brotherhood of Satan (1971), a Black Saint favorite from the producing team (L.Q. Jones and Alvy Moore) that brought you A Boy and His Dog (1975).

Decades of Horror 1970s Episode 181 – The Brotherhood of Satan (1971)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

A family is trapped in a desert town by a cult of senior citizens who recruit the town’s children to worship Satan.

Director: Bernard McEveety

Writers: William Welch; Sean MacGregor (original story by); L.Q. Jones (uncredited)

Selected cast:

Strother Martin as Doc Duncan

L. Q. Jones as Sheriff

Charles Bateman as Ben

Ahna Capri as Nicky

Charles Robinson as Priest

Alvy Moore as Tobey

Helene Winston as Dame Alice

Joyce Easton as Mildred Meadows

Debi Storm as Billie Joe

Jeff Williams as Stuart

Judy McConnell as Phyllis

Robert Ward as Mike

Geri Reischl as K. T.

Back in the fall of 2013, just prior to launching Gruesome Magazine, Doc’s cohost on Horror News Radio, Santos Ellin, Jr., The Black Saint, joined him on the Monster Movie Podcast to discuss their favorite films of the Seventies. Exploring two films from each year between 1970 and 1979, this two-episode retrospective would give birth to Decades of Horror 1970s.

For the year 1971, Santos picked The Brotherhood of Satan featuring Strother Martin, L.Q. Jones, Alvy Moore, and Charles Bateman. At long last, the Grue-Crew set their eyes on this often overlooked classic. The film holds up amazingly well over 50 years later, spotlighting Martin chewing the scenery in style and featuring some impressive cinematography. Seriously, only Strother Martin can handle dialog such as this and keep a straight face while delivering these lines and looking so menacing.

At the time of this writing, The Brotherhood of Satan is available to stream from Tubi and a variety of other PPV options. Regarding physical media, the film is currently available as a Blu-ray from Arrow Video.

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1970s is part of the Decades of Horror two-week rotation with The Classic Era and the 1980s. In two weeks, the next episode in their very flexible schedule, chosen by Bill, will be The Ghoul (1975), a Tyburn Films production directed by Freddie Francis starring Peter Cushing, Veronica Carlson, and John Hurt. Gotta be good, right?

We want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror 1970s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

1 note

·

View note